@nataliapc/mcp-openmsx

Version:

Model context protocol server for openMSX automation and control

528 lines (354 loc) • 50.7 kB

Markdown

# V9938 VRAM timings

Measurements done by: Joost Yervante Damad, Alex Wulms, Wouter Vermaelen

Analysis done by: Wouter Vermaelen

Text written by: Wouter Vermaelen

with help from the rest of the openMSX team.

## Introduction

This text describes in detail how, when and why the V9938 reads from and writes to VRAM in bitmap screen modes (screen 5, 6, 7 and 8). VRAM is accessed for bitmap and sprite rendering but also for VDP command execution or by CPU VRAM read/write requests.

### Motivation

Modern MSX emulators like blueMSX and openMSX are already fairly accurate. And for most practical applications like games or even demos they are already good enough. Though there are cases where you can still clearly see the difference between a real and an emulated MSX machine.

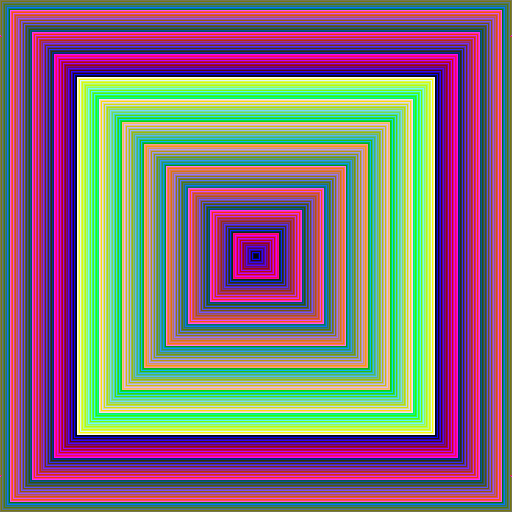

For example the following pictures show the speed of the LINE command for different slopes of the line. The first two pictures are generated on different MSX emulators, the last picture is from a real MSX. Without going into all the details: lines are drawn from the center of the image to each point at the border. While the LINE commands are executing, the command color register is rapidly changed (at a fixed rate). So faster varying colors indicate a slower executing command.

From left to right these pictures show:

- (left) The output of MSX emulators that use Alex Wulms' original command engine emulation core. All(?) modern MSX emulators use this core, including blueMSX, OCM and (older versions of) openMSX. The output are squares, this indicates that the speed of a LINE command doesn't depend on the slope of the line.

- (center) The output of openMSX version 0.9.1. Here the command engine was tweaked to take the slope of the line into account, so the test now generates clean octagonals.

- (right) The output of a real MSX. The overall shape is also an octagonal. But there are also a lot of irregularities. These irregularities can be reproduced when running the test multiple times. So it must be a real effect, and not some kind of measurement noise.

This test is derived from NYRIKKI's test program described in this (long) [MRC forum thread](http://www.msx.org/forum/msx-talk/software-and-gaming/line). This particular test is not that important. But because it generates a nice graphical output it allows to show the problem without going into too much technical details (yet).

In most MSX applications these LINE speed differences, or small command speed differences in general, likely won't cause any problems. (Except of course in programs like this that specifically test for it.) But it would still be nice to improve the emulators.

### Measurements

To be able to improve openMSX further we need to have a good understanding of what it is exactly that causes these irregularities. It would be very hard to figure out this stuff only by using MSX test programs. It might be easier to look at the deeper hardware level. More specifically at the communication between the VDP (V9938) and the VRAM chips. This should allow us to see when exactly the VDP reads or writes which VRAM addresses.

So at the 2013 MSX fair in Nijmegen we (some member of the openMSX team and I) connected a logic analyzer to the VDP-VRAM bus in a Philips NMS8250 machine. The following picture gives an impression of our measurement setup.

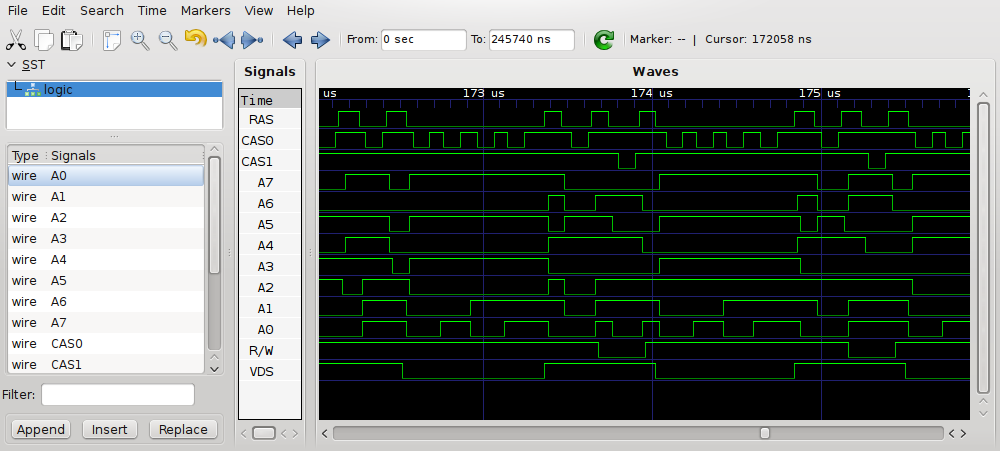

Next we ran some MSX software that puts the VDP in a certain display mode. It enables/disables screen and/or sprite rendering. And it optionally executes VDP commands and/or accesses VRAM via the CPU. And while this test was running we could capture (small chunks of) the communication between the VDP and the VRAM. This gives us output (waveforms) like in the following image.

It's not so easy to go from this waveform data to meaningful results about how the VDP operates. This text also won't talk about this analysis process. If you're interested in the analysis or in the raw measurement data, you can find some more details in the [openmsx-devel mailinglist archive](https://sourceforge.net/mailarchive/message.php?msg_id=30375119). The rest of this text will only discuss the final results of the analysis.

Because one of the primary goals was to improve the command engine emulation in openMSX, the measurements mostly focused on the bitmap screen modes (a V9938 doesn't allow commands in non-bitmap modes). So the following sections will only occasionally mention text or character modes. Because we used a V9938 we also couldn't test the YJK modes (screen 11 and 12). But it's highly likely that, from a VRAM access point of view, these modes behave the same as screen 8 (or as we'll see later, the same as all the bitmap screen modes).

## VRAM accesses

Before presenting the actual results of (the analysis of) the measurements, this section first explains the general workings of the VDP-VRAM communication. This is mostly a description of the functional interface of DRAM chips, but then specifically applied to the VDP case. Feel free to skim (or even skip) this section.

Like most RAM chips in MSX machines, the VDP uses DRAM chips for the video RAM. There exist many variations in DRAM chips. You can find a whole lot of information on [wikipedia](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dynamic_random-access_memory). Most of the info in this section can also be found in the 'V9938 Technical Data Book'. Often that book goes into a lot more detail than this text. Here I highlight (and simplify) the aspects that are relevant to understand the later sections in this text.

### Connection between VDP and VRAM

Between the VDP and the VRAM chips there is an 8-bit data bus. This means that a single read or write access will transfer 1 byte of data.

There is also an 8-bit address bus. Obviously 8 bits are not enough to address the full 128kB or even 192kB VRAM address space. Instead the address is transferred in two steps. First the row-address is transferred followed by the column address. (Usually) the row address corresponds to bits 15-8 of the full address, while the column address corresponds to bits 7-0.

Though this still only allows to address up-to 64kB. To get to 128kB, there are 2 separate column-address-select signals (named CAS0 and CAS1). These two signals allow to select one of the two available 64kB banks. So combined this gives 128kB. (Usually) you can interpret CAS0/CAS1 as bit 16 of the address.

In case of a MSX machine with 192kB VRAM there is still a third signal: CASX. To simplify the rest of this text, this possibility is ignored. It anyway doesn't fundamentally change anything.

Next to the data and address bus there are still some control signals. I've already mentioned the CAS signals (used to select the column address). There's a similar RAS (row address select) signal. And finally there's a R/W (read-write) signal that indicates whether the access is a read or a write.

### Timing of the VDP-VRAM signals

When the VDP wants to read or write a byte from/to VRAM it has to wiggle the signals that connect the VDP to the VRAM in a certain way. This section describes the timing of those wiggles.

The timing description in this section is different from the description in the 'VDP Technical Data Book'. The Data Book has the real timings, including all the subtle details for how to build an actual working system. This text has all the timings rounded to integer multiples of VDP clock cycles. IMHO these simplified timings make the VDP-VRAM connection easier to understand from a functional point of view.

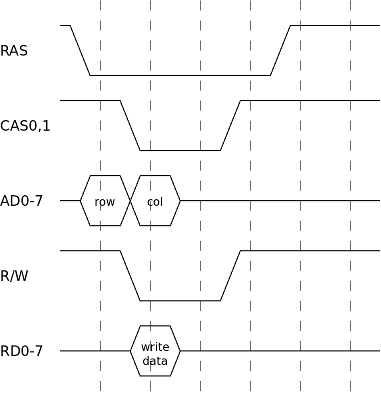

#### A single write

To write a single byte to VRAM, follow this schema:

- Put the row address on the address bus and activate the RAS signal. Most signals are active-low, so activating means make the signal low.

- After one cycle (remember these are functional timings, especially in this step the real timing rules are more complex):

- Activate (one of) the CAS signals.

- Put the column address on the address bus.

- Set the R/W signal. A low signal means write.

- Put the to-be-written data on the data bus.

- After two cycles the CAS signal can be deactivated. At this point the value of the R/W signal doesn't matter anymore (it may have any value). But measurements show that the VDP restores the R/W signal to a high value at this point.

- Again one cycle later, the RAS signal can be deactivated.

- The RAS signal has to remain de-active for at least two cycles.

So a full write cycle takes 6 VDP clock cycles.

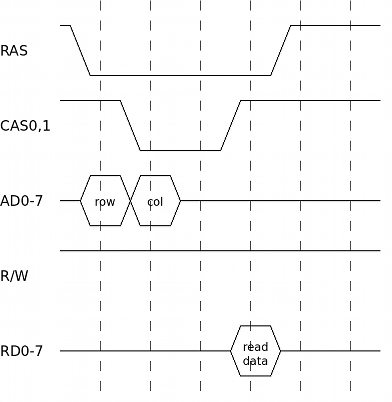

#### A single read

Reads are very similar to writes, they follow this schema:

- Put the row address on the address bus and activate the RAS signal.

- After one cycle:

- Activate (one of) the CAS signals.

- Put the column address on the address bus.

- Set the R/W signal: a high value indicates a read. The VDP keeps this signal high between VRAM transactions. So in measurements you don't actually see this signal changing for reads.

- After two cycles the read data is available on the data bus. The CAS signal can be deactivated now.

- After one cycle the RAS signal can be deactivated.

- Wait at least two cycles before starting the next VRAM transaction.

So this is very similar to a write: address selection is identical. Obviously the R/W signal and the direction (and timing) of the information on the data bus is different. And just like a write, a full read cycle also takes 6 VDP cycles.

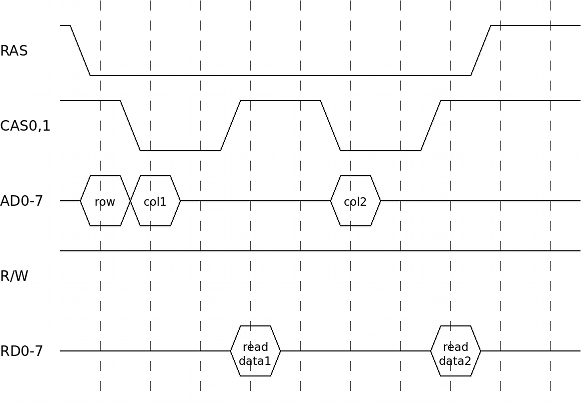

#### Page mode reads (burst read)

Often the VDP needs to read data from successive VRAM addresses. If those addresses all have the same row address, then there's a faster way to perform this compared to doing multiple reads like in the schema above.

- Put the (common) row address on the address bus and activate the RAS signal.

- After one cycle:

- Put the first column address on the address bus.

- Activate (one of) the CAS signals.

- Set the R/W signal (though the VDP already has this signal in the correct state).

- After two cycles read the data from the data bus, and deactivate CAS.

- Two cycles later, put the 2nd column address on the address bus and re-activate (one of) the CAS signals.

- Again two cycles later read the data and deactivate CAS.

- It's possible to repeat this process for a 3rd, 4th, … byte.

- After one cycle deactivate the RAS signal.

- Wait at least two cycles before starting the next VRAM transaction.

The above diagram shows a burst-length of only two bytes. It's also possible to have longer lengths. The VDP uses lengths up-to 4 bytes (or 8, see next section).

In this example reading two bytes takes 10 VDP cycles. Doing two single reads would take 2×6=12 cycles. When doing longer bursts, the savings become bigger. Doing a burst of N reads takes 2+4×N cycles compared to 6×N cycles for a sequence of single reads.

In principle it's also possible to do burst-writes. Though the VDP doesn't use them (it never needs to write more than 1 byte in a sequence).

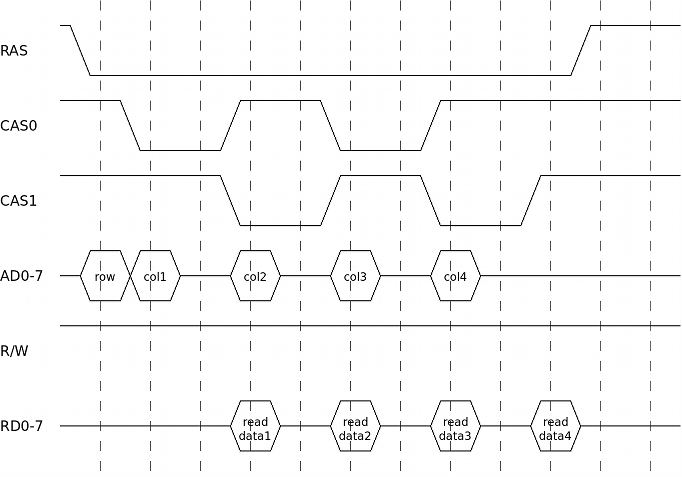

#### Multi-bank page mode reads

Burst reads are already faster than single-reads. But to be able to render screen 7 and 8 images, burst reads are still not fast enough. In these two screen modes, to be able to read the required data from VRAM fast enough, the VDP reads from two banks in parallel.

There are 2 banks of 64kB. These two banks share the RAS control signal, but they each have their own CAS signal. The address and data signals are also shared. This allows to read from both banks almost in parallel:

- In burst mode it was possible to read one byte every 4 VDP cycles. For this the CAS signal had two be alternatingly two cycles high and two cycles low. The address and data buses are only used during 1 of these 4 cycles.

- Multi-bank mode uses both the CAS0 and the CAS1 signals. CAS0 is high when CAS1 is low and vice-versa. When looking at a single bank (which only sees one of the two CAS signals) this looks like a normal burst read. The only difference is that the RAS signal is at the start or at the end 2 cycles longer active than strictly needed. But that's perfectly fine.

So this schema gives (almost) double the VRAM-bandwidth. The only requirement is that you alternatingly read from bank0 and bank1. At first sight this requirement seems so strict that it is almost never possible to make use of this banked reading mode: to render screen 7 or 8 you indeed need to read many successive VRAM locations, not locations that alternatingly come from the 1st and 2nd 64kB bank.

To make it possible to use banked reading mode, the VDP interleaves the two banks. This introduces the concept of logical and physical addresses:

- Logical addresses are the addresses that a programmer of the VDP normally uses. For example the bitmap data for screen 8 (possibly) starts at address 0x00000 and goes till address 0x0D400.

- Physical addresses are the addresses that actually appear on the signals between the VDP and the VRAM. So the combination of the row and column address and the CAS0 or CAS1 bank-selection.

In most screen modes the logical and the physical addresses are the same. But in screen 7 and 8 there's a transformation between the two:

`physical = (logical >> 1) | (logical << 16)`

So the 17-bit logical address is rotated one bit to the right to get the physical address. The effect of this transformation is that all even logical addresses end up in physical bank0 while all odd logical addresses end up in physical bank1. So now when you read from successive logical addresses you read from alternating physical banks and thus it is possible to use banked read mode.

Usually a VDP programmer doesn't need to be aware of this interleaving. But because interleaving is only enabled in screen 7 and 8, this effect can become visible when switching between screen modes. _An alternative design decision could have been to always interleave the addresses. I guess the V9938 designers didn't make this choice to allow for single chip configurations in case only 64kB VRAM is connected._

The diagram above shows a read of 2×2 bytes, in reality the VDP only uses this schema to read 2×4 bytes. In principle it's also possible to write to two banks in parallel, but the VDP never needs this ability.

#### Refresh

DRAM chips need to be refreshed regularly. The VDP is responsible for doing this (there are DRAM chips that handle refresh internally, but the VDP doesn't use such chips). Many DRAM chips allow a refresh by only activating and deactivating the RAS signal, so without actually performing a read or write in between. When extrapolating from the above timing diagrams, this would only cost 4 cycles. Though the VDP doesn't actually use this RAS-without-CAS refresh mode. Instead it performs a regular read access which takes 6 cycles.

Each time a read (or write) is performed on a certain row of a DRAM chip, that whole row is refreshed. So to refresh the whole RAM, the VDP has to periodically read (any column address of) each of the 256 possible rows.

## Distribution of VRAM accesses

The previous section described the details of isolated (single or burst) VRAM accesses. This section will look at such accesses as indivisible units and examine how these units are grouped together and spread in time to perform all the VRAM related stuff the VDP has to do.

The VDP can perform VRAM reads/writes for the following reasons:

- Refresh

- Bitmap rendering

- Sprite rendering

- CPU read/write

- Command read/write

Note that next to bitmap modes, the VDP also has character and text modes. I didn't investigate those modes yet, so this text mostly ignores them.

The rest of this text explains when in time (at which specific VDP cycles) accesses of each type are executed.

We'll first focus on refresh and bitmap/sprite rendering. Later we'll add CPU and command engine. The reason for this split is that the first group has a fairly simple pattern: refreshes always occur at fixed moments in time. Enabling bitmap rendering only adds additional VRAM reads but has no influence on the timing of the refreshes. Similarly enabling sprite rendering adds even more reads without influencing the bitmap or refresh reads. CPU and command accesses on the other hand cannot simply be added to this schema without influencing each other. So those are postponed till a later section.

### Horizontal line timing

The VDP renders a full frame line-by-line. For each line the VDP (possibly) has to read some bitmap and sprite data from VRAM. It's logical to assume (and the measurements confirm this) that the data fetches within one line occur at the same relative positions as the corresponding data fetches of another line. So if we can figure out the details for one line, we can extrapolate this to a whole frame. Similarly we can assume that different frames will have similar relative timings. So really all we need to know is the timing of one line.

_TODO: odd and even frames in interlace mode probably do have timing differences. Still need to investigate this._

Let's thus first look at what we already know about an horizontal display line. The 'V9938 Technical Data Book' contains the following timing info about (non-text mode) display lines.

|Description|Cycles|Length|

|---|:-:|--:|

|Synchronize signal|[0 - 100)|100|

|Left erase time|[100 - 202)|102|

|Left border|[202 - 258)|56|

|Display cycle|[258 - 1282)|1024|

|Right border|[1282 - 1341)|59|

|Right erase time|[1341 - 1368)|27|

|Total|[0 - 1368)|1368|

So one display line is divided in 6 periods. The total length of one line is 1368 cycles. The previous section showed how long individual VRAM accesses take. The next sections will figure out how all the required accesses fit in this per-line budget of 1368 cycles.

A note about the timing notation: in this text all the timing numbers are VDP cycles relative within one line. For example in the table above the display period starts at cycle 258. The display period of the next line will start at cycle 258+1368=1626, the next at cycle 2994 and so on. To make the values smaller, all cycle numbers will be folded to the interval [0, 1368). The staring point (cycle=0) has no special meaning. We could have taken any other point and called that the starting point. (For the current choice, the external VDP HSYNC pin gets activated at cycle=0, so it was a convenient point to synchronize the measurements on).

_TODO horizontal set-adjust: The numbers in the above table are valid for horizontal set-adjust=0. Similarly all our measurements were done with set-adjust=0. Using different set-adjust values will make the left/right border bigger/smaller. I still need to figure out which timing values of the next sections are changed by this. E.g. are all the VRAM accesses in a line shifted as a whole, or are just the bitmap data fetches shifted and remain (some) other accesses fixed?_

_TODO bits S1,S0 in VDP register R#9: The above table is valid for S1,S0=0,0. In other cases the length of a display line is only 1365 cycles instead of 1368. The rest of this text assumes a line length of 1368 cycles. I still need to figure out where exactly in the line this difference of 3 cycles is located._

### Sneak preview

The following image graphically summarizes the results of the rest of this section. This is a very wide image, it is much larger than what can be shown inline in this text (click to see the full image). It's highly recommended to open this image in an external image viewer that allows to easily zoom in and out and scroll the image.

Here's an overview of the most important items in this image:

- Horizontally there are 6 regions in the image (each has a slightly different background color). These regions correspond to the 'synchronize', 'left/right erase', 'left/right border' and 'display' regions in the table from the previous section.

- Horizontally you also see a timeline going from 0 to 1368 cycles. This corresponds to one full display line.

- Vertically there are 3 big groups: 'screen off', 'no sprites' and 'sprites', see next section for why these groups are important.

- Within one vertical group there is one color-coded band and a set of RAS/CAS signals. Usually there's one RAS and 2 CAS signals, but the 'sprites off' group has 2 pairs of CAS signals. For the 'sprites off' and 'sprites on' groups there are subtle differences in the CAS0/1 signals between screen modes 5/6 and 7/8. But to save space these differences are only shown once.

- The colors in the color-coded band have the following meaning:

- red: refresh read

- green: bitmap data read (dark-green is dummy bitmap read)

- yellow: sprite data read (brown is dummy sprite read)

- blue: potential CPU or command engine read or write

- dark-grey: dummy read

- light-gray: idle (no read or write)

- The CAS signals are drawn in either a full or a stippled line. Full means the signal is definitely high/low at this point. Stippled means, it can be high or low depending on whether there was a CPU request or VDP command executing at that point. Note that the RAS signal always toggles, even if there is no CPU or command access required.

The next sections will go into a lot more detail. It's probably a good idea to have this (zoomed in) image open while reading those later sections.

### 3 operating modes

When looking from a VDP-VRAM interaction point of view, the VDP can operate in 3 modes:

- Screen disabled (sprite status doesn't matter). This is the same as vertical border.

- Screen enabled, sprites disabled.

- Screen enabled, sprites enabled.

Note that the (bitmap) screen mode (screen 5, 6, 7, or 8) largely doesn't matter for the VRAM access pattern.

_TODO sprite fetching happens 1 line earlier than displaying those sprites (see below for details). This means that the last line of the vertical border before the display area likely uses a 'mixed mode' where it doesn't yet fetch bitmap data but it does already fetch sprite data. I didn't specifically measure this condition, so I can't really tell anything about this mixed mode. (One possibility is that it's just like a normal display line, but the fetched bitmap data is ignored.) Similarly the last line of the display area doesn't strictly need to fetch new sprite data._

We'll now look at these 3 modes in more detail.

#### Screen disabled

##### refresh

Screen rendering can be disabled via bit 6 in VDP register R#1. There's also no screen rendering when the VDP is showing a vertical border line. From a VRAM-access point of view both cases are identical.

In this mode the VDP doesn't need to fetch any data from VRAM for rendering. It only needs to refresh the VRAM. As already mentioned earlier, the VDP uses a regular read to refresh the RAM, so this takes 6 cycles.

The VDP executes 8 refresh actions per display line. They start at the following moments in time (the red blocks in the big timing diagram):

`284 412 540 668 796 924 1052 1180`

##### refresh-addresses

I didn't investigate this refresh-address-stuff in detail because it doesn't matter for emulation accuracy.

The logical addresses used for refresh reads seems to be of the form:

`N×0x10101 | 0x3F`

Where N increases on each refresh action. So each refresh the row address increases by one and every other refresh either the CAS0 or the CAS1 signal gets used (the columns address doesn't matter for refresh). Note that this formula is for the logical address, in screen 7/8 this still gets transformed to a physical address. So in screen 7/8 a refresh action always uses the CAS1 signal. That means that in screen 7/8 the DRAM chip(s) of bank0 actually do get refreshed using the RAS-without-CAS refresh mode.

The refresh timings are the same for all non-text screen modes. But in text modes there are only 7 refreshes per line and they are also located at different relative positions than in the table above. I didn't investigate this further.

##### dummy reads

Next to the refresh reads, in 'screen disabled' mode, the VDP still performs 4 reads of address 0x1FFFF. At the following moments (marked with dark-grey blocks on the timeline):

`1236 1244 1252 1260`

I can't image any use for these reads, so let's call them dummy reads. In all our measurements these dummy reads always re-occur in these same positions, so it's not a fluke in (only one of) the measurements.

The refresh actions remain exactly the same in the other two modes. But these dummy reads are different in the mode 'sprites off' or disappear completely in the mode 'sprites on'. (This confirms that nothing 'useful' is done by these dummy reads).

Anyway for emulation we can mostly ignore these dummy reads. It only matters that at these moments in time there cannot be CPU or command VRAM reads or writes.

#### screen enabled, sprites disabled

##### refresh and dummy reads

Refresh works exactly the same as in the previous mode. The dummy reads are a bit different. Now there are only 3 dummy reads at slightly different moments (also shown in dark-grey):

`1242 1250 1258`

The first of these 3 reads is always from address 0x1FFFF. The second and third dummy read have a pattern in their address. For example:

|1st|2nd|3rd|

|---|---|---|

|0x1FFFF|0x03B80|0x03B82|

|0x1FFFF|0x03C00|0x03C02|

|0x1FFFF|0x03C80|0x03C82|

|0x1FFFF|0x03D00|0x03D02|

This table shows the addresses of the 3 dummy reads for 4 successive display lines (this is data from an actual measurement, unfortunately our equipment could only buffer up to 4 lines). The lower 7 bits of the address of the 2nd read always seem to be zero. The address of the 3rd read is the same as for the 2nd read except that bit 1 is set to 1. When going from one line to the next, the address increases by 0x80. Our measurements captured 10 independent sets of 4 successive lines. Each time bits 16-15 were zero (bits 14-7 do take different values). This could be a coincidence, or it could be that these bits really aren't included in the counter. Note that again these are logical addresses (so still transformed for screen 7/8). I didn't investigate these dummy reads in more detail because they mostly don't matter for emulation.

##### bitmap reads

The major change compared to the previous mode is that now the VDP needs to fetch extra data for the bitmap rendering. These fetches happen in 32 blocks of 4 bytes (screen 5/6) or 8 bytes (screen 7/8). The fetches within one block happen in burst mode. This means that one block takes 18 cycles (screen 5/6) or 20 cycles (screen 7/8). Though later we'll see that the two spare cycles for screen 5/6 are not used for anything else, so for simplicity we can say that in all bitmap modes a bitmap-fetch-block takes 20 cycles. This is even clearer if you look at the RAS signal: this signal follows the exact same pattern in all (bitmap) screen modes, so in screen 5/6 it remains active for two cycles longer than strictly necessary.

Actually before these 32 blocks there's one extra dummy block. This block has the same timing as the other blocks, but it always reads address 0x1FFFF. From an emulator point of view, these dummy reads don't matter, it only matters that at those moments no other VRAM accesses can occur.

The start of these 1+32 blocks are located at these moments in time (these are the green blocks in the big timing diagram):

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|(195)|227|259|291|323|355|387|419|451|

||483|515|547|579|611|643|675|707|

||739|771|803|835|867|899|931|963|

||995|1027|1059|1091|1123|1155|1187|1219|

_The following is only speculation: I wonder why there is such a dummy preamble block. Theoretically this could have been used (or reserved) to implement V9958-like horizontal scrolling without having to mask 8 border pixels. Unfortunately horizontal scrolling on a V9958 doesn't work like that :(_

#### screen enabled, sprites enabled

##### refresh, dummy reads, bitmap reads

Refresh and bitmap reads are exactly the same as in the previous mode. But the 3 or 4 dummy reads from the previous 2 modes are not present in this mode.

##### sprite reads

I've only investigated bitmap modes, that means the stuff below applies only to sprite mode 2.

For sprite rendering you need to:

- Figure out which sprites are visible: There are 32 positions in the sprite attribute table, and of those maximum 8 sprites can be visible (per line).

- For the visible sprites, fetch the required data so that it can actually be drawn. This data is: the x- and y-coordinates, the sprite pattern number, the pattern data and the color data.

Figuring out which sprites are visible is done by reading the y-coordinates of each of the 32 possible sprites. These reads happen interleaved between the 32 block-reads of the bitmap data, so read one byte between each bitmap-block. Because of this interleaving it's not possible to use burst mode, so each read takes 6 cycles. There's also 1 dummy read of address 0x1FFFF at the end. The reads happen at these moments in time (yellow blocks between the green blocks in the diagram):

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|182|214|246|278|310|342|374|406||

|438|470|502|534|566|598|630|662||

|694|726|758|790|822|854|886|918||

|950|982|1014|1046|1078|1110|1142|1174|(1206)|

In the worst case, the 8 last sprites of the attribute table are visible. In that case all 32 reads are really required. Though even if the limit of 8 visible sprites is reached earlier, the VDP continues fetching all 32+1 bytes. Also if one y-coordinate is equal to 216 (meaning that all later sprites are invisible), still all 32+1 fetches are executed.

Once the VDP has figured out which sprites are visible it needs to fetch the data to actually draw the sprites. This VRAM access pattern is relatively complex:

- In the worst case there are 8 visible sprites. This requires reading 8×6 bytes. Some of these reads can be done in burst mode, others are single byte reads.

- Even if there are less than 8 sprites to display, all read accesses do still occurs. It seems to be that the useless reads are duplicates of sprite 0. (Or is it the first visible sprite? I didn't look in detail because it's not important for our purpose. It only matters that the VRAM bus remains occupied).

- The data fetches happens in 4 chunks of each 2 sprites. Each chunk reads:

- Y-coordinate, x-coordinate and pattern-number of 1st sprite. Burst of 3 reads, takes 13(!)cycles.

- Y-coordinate, x-coordinate and pattern-number of 2nd sprite. Burst of 3 reads, takes 13(!)cycles.

- Pause of 6 or 10(!) cycles

- 2 pattern bytes of 1st sprite. Burst of 2 reads, takes 10 cycles.

- Color attribute of 1st sprite. Single read, takes 6 cycles.

- 2 pattern bytes of 2nd sprite. Burst of 2 reads, takes 10 cycles.

- Color attribute of 2nd sprite. Single read, takes 6 cycles.

- Note that the burst of 3 reads only takes 13 instead of the expected 14 cycles. If you look at the RAS/CAS signals you see that this uses an illegal(?) RAM access pattern: RAS is released together with CAS (even slightly before if you look at the raw measured data). But obviously this seems to work fine … makes me wonder why the VDP doesn't always use this faster access pattern.

- Even for 8x8 sprites, the VDP always fetches 2 bytes of pattern-data per sprite line (and the 2nd byte is ignored).

- Note that the y-coordinate is fetched again. It was already fetched to figure out which sprites are visible.

- The positions in time of these reads (single or burst) are like this (yellow blocks (mostly) in the border period in the big timing diagram):

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|1238|1251|1270|1280|1286|1296|

|1302|1315|1338|1348|1354|1364|

|2|15|34|44|50|60|

|66|79|98|108|114|124|

- Note that some of these fetches occur in the previous and some in the current display line. Though the start of the display line was chosen arbitrary (we could have picked the staring point so that these numbers don't wrap). It only matters that all sprite data is fetched before the display rendering starts.

- Also note that the timing is slightly irregular: in the 1st, 3rd and 4th group there's a pause of 6 cycles, there fits exactly one other access in this gap. But in the 2nd group there's a pause of 10 cycles. There also only fits one other access in this gap, and the timing is 2+6+2, so 2 'wasted' cycles before and after that other access. I suspect that these 2+2 cycles are related to the R#9 S1,S0 bits. TODO measure this.

It's worth repeating that whenever sprites are enabled, the VDP always performs the same fetch-pattern. So even if no sprites are actually visible, or if sprites are partially disabled (with y=216), and even with 8x8 vs 16x16 sprites, magnified or not. This confirms the fact that the VDP command engine is slowed down by the exact same amount in all these situation. Also all (bitmap) screen modes behave exactly the same with respect to sprite data fetches.

### CPU and command reads/writes

##### position of access slots

The previous sections explained when the VDP reads from VRAM for refresh and bitmap/sprite rendering (and even some dummy reads). Depending on the mode (screen/sprites enabled/disabled), this takes more or less of the available VRAM-bandwidth. The portion of the VRAM bandwidth that is not used for rendering can be used for CPU or command engine VRAM reads or writes.

All CPU and command engine accesses are single (non-burst) accesses, so they take 6 cycles each. However it is not the case that whenever the VRAM bus is idle for 6 cycles, it can be used for CPU or command engine accesses.

Instead there are fixed moments in time where there could possibly start a cpu or command access, let's call these moments access slots. Each slot can be used for either CPU or command accesses (there are no slots that are uniquely reserved for either CPU or for commands). The position and the amount of access slots only depends on the VDP mode (screen off, sprites off, sprites on), not for example on the amount of actually visible sprites or on the (bitmap) screen mode.

The 3 tables below show the amount and the positions of the possible access slots for the 3 different modes (in the timing diagram these are the blue blocks):

**screen off, 154 possible slots**

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|0|8|16|24|32|40|48|56|64|72|

|80|88|96|104|112|120|164|172|180|188|

|196|204|212|220|228|236|244|252|260|268|

|276|292|300|308|316|324|332|340|348|356|

|364|372|380|388|396|404|420|428|436|444|

|452|460|468|476|484|492|500|508|516|524|

|532|548|556|564|572|580|588|596|604|612|

|620|628|636|644|652|660|676|684|692|700|

|708|716|724|732|740|748|756|764|772|780|

|788|804|812|820|828|836|844|852|860|868|

|876|884|892|900|908|916|932|940|948|956|

|964|972|980|988|996|1004|1012|1020|1028|1036|

|1044|1060|1068|1076|1084|1092|1100|1108|1116|1124|

|1132|1140|1148|1156|1164|1172|1188|1196|1204|1212|

|1220|1228|1268|1276|1284|1292|1300|1308|1316|1324|

|1334|1344|1352|1360|||||||

**sprites off, 88 possible slots**

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|6|14|22|30|38|46|54|62|70|78|

|86|94|102|110|118|162|170|182|188|214|

|220|246|252|278|310|316|342|348|374|380|

|406|438|444|470|476|502|508|534|566|572|

|598|604|630|636|662|694|700|726|732|758|

|764|790|822|828|854|860|886|892|918|950|

|956|982|988|1014|1020|1046|1078|1084|1110|1116|

|1142|1148|1174|1206|1212|1266|1274|1282|1290|1298|

|1306|1314|1322|1332|1342|1350|1358|1366|||

**sprites on, 31 possible slots**

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|28|92|162|170|188|220|252|316|348|380|

|444|476|508|572|604|636|700|732|764|828|

|860|892|956|988|1020|1084|1116|1148|1212|1264|

|1330||||||||||

Note that even in the mode 'screen off', when the VRAM bus is otherwise mostly idle, the access slots are still at least 8 cycles apart. A single access takes only 6 cycles, so 2 cycles are wasted.

Very roughly speaking in mode 'screen off' there are about twice as many access slots as in the mode 'sprites off' and about 5 times as many as in the mode 'sprites on'. This does however not mean that in these modes the command engine will execute respectively 2× and 5× as fast. Instead in the mode 'sprites on' the speed of command execution is mostly limited by the amount of available access slots, while in the mode 'screen off', the bottleneck is mostly the speed of the command engine itself.

Also note that the access slots are not evenly spread in time. For example:

- In mode 'screen off', the slots are often only 8 cycles apart (measured from the start of the 1st to the start of the 2nd slot). Though starting at cycle=120 there's a gap of 44 cycles.

- In mode 'sprites off', during the horizontal border, the access slots are roughly 8 cycles apart like in the previous mode, but during the display period, the spacing is more like 26 or 32 cycles. The largest gap is now 54 cycles starting at cycle=1212.

- In mode 'sprites on', the pattern is again completely different. Here the slots are roughly 32 or 64 cycles apart. (The border even has slightly larger gaps than the display area. So contrary to some speculations, the commands do not execute faster in the horizontal border in this mode). The largest gap is now 70 cycles, starting at cycle=92. There's even one location where the smallest gap is also only 8 cycles. (Though if you look at the measurements you'll see that the slot right after this smallest gap (at cycle=170) is rarely actually used, even though the command engine is starved for VRAM bandwidth).

These large gaps between the access slots are important. For example if the CPU is sending data to the VDP at a too fast rate, and this happens right at a moment where there are no access slots available, then some of the data send by the CPU is lost. We'll see later in this text that this can even happen when the time between the incoming CPU requests is (slightly) larger than the size of the largest gap.

##### allocation of access slots

The access slots can be used for either CPU or VDP command reads or writes. This section explains how the slots are allocated to these two subsystems.

The basic principle is very simple: the CPU or the command engine take the first available access slot. And when the CPU and command engine both require an access slot at the same time, then the CPU gets priority. Though if you look at the details it is a bit more complicated:

- When the CPU sends a read or write VRAM request to the VDP, this request is put in a buffer until it can be handled.

- When the CPU sends a new request when there's still a previous request pending then the old request is lost. More on this below. TODO most logical is that the old (not the new) request is lost, but actually check this. Though the Z80 might be too slow to be able to test this.

- Similarly when the VDP command engine needs to perform a VRAM read or write, this request is also put in a buffer. This is a different buffer than the one for CPU requests.

- In contrast to the CPU, the command engine is stalled when the command engine buffer holds a request. So command engine requests can never get lost.

- 16 cycles in advance of an access slot the VDP checks whether there is either a pending CPU or command request. If there's a pending CPU request, that request will be executed (16 cycles later). If there's no cpu request but there is a command request then that one will be executed (16 cycles later). So the CPU takes priority over the command engine. And very important, if there's no request pending yet, then 16 cycles later nothing will be executed, not even if a request does arrive within 16 cycles.

##### cpu access slows down command execution

A surprising result (at least to me) of these measurements is that the speed of VDP command execution is reduced while simultaneously doing CPU VRAM accesses. Looking back this makes sense because the same VRAM access slots are shared between CPU and command engine and the CPU gets priority.

This effect is clearly noticeable in the mode 'sprites on' but much less in the other two modes. This is easily explained by looking at the amount of available access slots in these modes.

The most extreme situation occurs in this test. Execute a HMMV VDP command (this is the fastest command, see below) while simultaneously executing a long series of OUT (#98),A instructions (the fastest way to send CPU write requests). In our measurements, in the mode 'sprites on' the command execution speed was approximately cut in half! But in the other two modes, the execution speed was barely influenced. (Actually our test program wasn't accurate enough to measure any significant speed difference, but theoretically also in the latter two modes the execution speed should be reduced by a small amount).

##### too fast CPU access

The fastest way for the Z80 to send read or write VRAM request to the VDP is by using a sequence of IN A,(#98) or OUT (#98),A instructions (of course such a sequence always writes the same value or ignores all but the last read value). This takes 12 Z80 clock cycles per request. (Instructions like OUT (C),r or OUTI are all slower). The VDP is clocked at 6× the Z80 speed. So when the Z80 sends multiple requests to the VDP, the minimal distance between these requests, translated to VDP cycles, is at least 72 VDP cycles. Earlier we saw that the maximal gap between access slots was 70 VDP cycles, so at first sight there's no problem. However consider this scenario:

- Suppose we're in 'sprites on' mode. At time=236, we're 16 cycles before an access slot. Suppose there's no pending CPU nor command request at this time. So nothing will get executed at time=252.

- A bit later at time=240 there arrives a CPU write request. This request gets buffered.

- At time=252 there is an access slot, but nothing will get executed in this slot (because this slot wasn't allocated at time=236).

- At time=300 we're again 16 cycles before an access slot. Now there is a pending CPU request, so we'll execute that at time=316.

- At time=312 we receive a new CPU write request. This is 312-240=72 VDP cycles (or 12 Z80 cycles, the duration of a OUT (#98),A instruction) after the previous request. But the buffer still contains the previous unhandled request. The new request overwrites the old request!

- At time=316 there's an access slot and we've allocated this slot to the CPU (at time=300). So the pending CPU request gets executed. Though this writes the data from the new request, the data from the old request is never written!

Note that this scenario used a gap of only 64 VDP cycles between access slots, while there were 72 cycles between the CPU requests. (And the largest gap between access slots is 70 cycles).

## Command engine timing

The command engine needs access to VRAM. In the previous section we saw when the VDP will grand access to this subsystem: when there's an access slot available and when that slot is not already allocated to CPU access. In this section we'll see when exactly the command engine will generate VRAM access requests. Obviously the type (read or write) and the rate of these requests depends on the type of the VDP command that is executing.

Some commands (like HMMV) only need to write to VRAM. Other commands (like LMMM) need 2 reads and 1 write per pixel. Many commands execute on a block (a rectangle) of pixels. Such a block is executed line per line (all pixels within one horizontal line are processed before moving to the next line). Moving from one line to the next takes some amount of time (but YMMM is an exception, see below). This means that e.g. a HMMM command on a 20x4 rectangle executes faster than on a 4x20 rectangle (same amount of pixels in both cases, but a different rectangle shape).

The following table summarizes the timing for all measured commands:

|Command|Per pixel|Per line|

|---|---|---|

|HMMV|48 W|56|

|YMMM|40 R 24 W|0|

|HMMM|64 R 24 W|64|

|LMMV|72 R 24 W|64|

|LMMM|64 R 32 R 24 W|64|

|LINE|88 R 24 W|32|

_TODO timing for PSET, POINT, SRCH_

I'll explain the notation in this table with an example. Take the LMMM command:

- Per pixel the LMMM command needs to:

- Read a byte from the source.

- Read a byte from the destination

- Calculate the result: extract the pixel value from source and destination, combine the two (possibly with a logical operation), insert the result in the destination byte. And write the result back to the destination.

- So per pixel, the LMMM command will generate 3 VRAM accesses: 2 read followed by one write. Between these accesses there will be some amount of time.

- For LMMM the table lists '64 R 32 R 24 W'. Let's start at the 1st 'R' character, this represents the 1st read. Next there's the value 32 and a 2nd 'R', this means that the 2nd read comes at least 32 cycles after the 1st read. Then there's '24 W', meaning there are at least 24 cycles between the 2nd read and the write. And the initial value '64' means that there are at least 64 cycles between the write and the 1st read for the next pixel.

- When moving from one horizontal line to the next in a block command, there is some extra delay. For the LMMM command this takes 64 extra cycles. So 64+64=128 cycles from the last write of a line till the first read of the next line.

- Note that all these values are the optimal timing values. The actual delay can be longer because there is no access slot available or the slot is already allocated for CPU access.

All the commands in the table above are block commands except for 'LINE'. For the LINE command the meaning of the columns 'Per pixel' and 'Per line' may not be immediately clear:

- The VDP uses the Bresenham algorithm the calculate which pixels are part of the line.

- This algorithm takes at each iteration one step in the major direction. The timings for such an iteration are written in the 'Per pixel' column for the LINE command.

- Depending on the slope of the line, in some iterations the Bresenham algorithm also takes a step in the minor direction. For the VDP such a minor step takes some extra time (32 cycles). This is written in the 'Per line' column of the LINE command. (If you look back at the very beginning of this text, these major and minor steps explain the general octagonal shapes in the images. The uneven distribution of the access slots explain the irregularities.)

Note that for the YMMM command there's no extra overhead when going from one horizontal line to the next. This might be related to the fact that a line of a YMMV command always starts at the left or right border of the screen.

_TODO What we didn't measure (also couldn't measure with our test setup) was the delay between the start of the command (when the CPU sends the command byte to the VDP) and the moment the command actually starts executing (e.g. when the first read or write command access is send to VRAM). It's logical to assume that the 'per line' overhead also occurs at the start of the command. But it's possible there is also some additional 'per command' overhead._

##### speculation on the slowness of the command engine

When looking at the above table, we see that the command engine is very slow. For example in a HMMM command there are 24 cycles between reading a byte and writing that byte to the new location. Or in a LINE command it takes 32 cycles to take a step in the minor direction. I believe there are two main reasons for this slowness:

I believe that internally the VDP command engine subsystem runs at 1/8 of the master VDP clock frequency. This matches the observation that all values in the above table are multiples of 8. It also explains why the access slots are always at least 8 cycles apart (while a VRAM access only requires 6 cycles).

The command engine gets stalled whenever there's a pending command engine VRAM request. A VRAM request (CPU or command) only gets handled after it's been pending for at least 16 cycles. So combined this means the command engine gets stalled for 16 cycles on every VRAM request it makes. (Note that especially this point is just speculation).

Taking these two points into account, the above table can be rewritten as:

|Command|Per pixel|Per line|

|---|---|---|

|HMMV|(4×8+16) W|7×8|

|YMMM|(3×8+16) R (1×8+16) W|0×8|

|HMMM|(6×8+16) R (1×8+16) W|8×8|

|LMMV|(7×8+16) R (1×8+16) W|8×8|

|LMMM|(6×8+16) R (2×8+16) R (1×8+16) W|8×8|

|LINE|(9×8+16) R (1×8+16) W|4×8|

When you look at the data in this way, the numbers already look more reasonable.

## Next steps

All the information above _should_ already be enough to significantly improve the accuracy of MSX emulators. The following months I plan to work on improving openMSX.

- First I'd like to improve the CPU-VRAM access stuff, so that e.g. too fast CPU accesses actually result in dropped requests.

- Next step is the timing of the VDP commands. This depends on the previous step because e.g. CPU access slows down command execution.

- Still a later step could be to more accurately in time fetch the data required for display rendering (bitmap, sprites). This is lower priority because:

- These effects are limited to the visual output. Errors can't influence the 'state' of the MSX machine. So it's impossible to write a MSX program that checks (= makes a decision based on) the rendering accuracy. (OTOH it is possible to check for dropped CPU requests or the speed of the commands).

- I don't know of any existing MSX software where this will make a noticeable difference. Maybe an idea fo